Having written a subversive action novel focusing on the lives and times of a cell of terrorists that some early readers indicated would make a great movie, I gave the project some thought and soon concluded that my story was a natural for film adaptation. It has a simple, linear plot with subplots to spare, featuring appealing, interesting characters, and mostly set in real places I didn’t have to make up, sharply limned in luminous detail.

Suspecting that there was more to writing for movies that I needed to know, I straightaway dove into the turbulent and treacherous waters of screenwriting, only to surface gasping over how ginormous and competitive, how overflowing with talent, copy, and potential productions the screenplay marketplace is. Not to mention the secondary markets for script consultants, synopsizers, agents, contests, how-to books, DVDs, webinars, and software products pawing at you to help you write screenplays that sell. Emerging from my brief and bewildering dip into these waters, it was close-up clear that to navigate a course to celluloid I needed to consult sage practitioners of this elusive art.

Somewhat prematurely, I engaged what’s called a script consultant, someone who evaluates stories to help authors maximize their success as screenplays. The one I latched onto was a friend of a friend in the biz who seemed eager to help. Two months and more than a few hundred dollars later, my consultant’s evaluation came in. I was informed that my novel had many great qualities but needed some work—a lot of work actually—to fulfill its cinematic potential. For example, too many scenes of conversations over meals:

I think everything about the story and the writing itself needs to get more serious. The dinner parties need to end – I don’t think the food would taste quite that good anymore – as their plan starts to become a reality.

Nor did the private thoughts of my characters and their expression sit well with my script expert:

You need to cut out much of the dialogue and add more action, more complications and reversals, more conflict and just basically more plot. You also need to figure out how to cinematically deal with the great deal of internal dialogue

Fine. So I skipped some meals, cut out snacks, and found ways to indicate interactions that took place there. I also ditched some private thoughts or fashioned them into gestures. This of course in the novel itself; I had already decided I wouldn’t try to adapt it to a screenplay until it was in better shape and I knew more about how to script. But then, real trouble:

This is a big missed opportunity. So much could be done with an authority trying to track this group down. On a pure plot level, you can have near misses and close calls. You have an opportunity to see the other side of things Adding an antagonist / cop will certainly add tension and stakes to the story. But more conflict is needed – specifically conflict between the jihadists themselves. The story does a nice job of bringing together different people with different backgrounds and different motives. But everyone, for the most part, seems to get along swimmingly. This simply isn’t interesting … We need schisms amongst the group. Real fights. … To make the story interesting and dramatic, we need more tension and suspicion in the group.

While my characters live in constant fear of state security, I never felt it would add much to personify a main adversary. And while they do have some differences it never gets down to shouting matches or fisticuffs. But I tried to get with the program by accentuating within-group conflicts and even added an antagonist to my female protagonist, although he never appears in person. And when I ran those changes by an experienced scriptwriter I later engaged with, I was told there still wasn’t enough conflict and tension to loft the plot onto the silver screen.

So perhaps it’s me, simply not understanding the art of screenplay. In search of cinematic wisdom, I trundled home from the library an armload of manuals hoping to learn the basis for all the critiques I was getting. It didn’t take long to find confirmation. Book after book of advice by screenplay industry gurus affirmed that my roller coaster of a plot went up and down too many molehills, and too slowly at that.

The gurus banged into my head what the script of a movie—any movie, tragic or comic—must have: Three Acts, the second longer than the other two; Plot Points, transitions where important events twist and turn the action; and something called the Big Event to end act one, preceded by an Inciting Incident that gives the protagonist a desire or goal to pursue. But wait—Plot Points don’t stop there! All in all, veteran script expert Dave Trottier tells us in The Screenwriter’s Bible, we shouldn’t settle for less than seven:

- Backstory—Exposes motivations and vulnerabilities

- Catalyst—The setup, or Inciting Incident

- Big Event—That life-changing moment

- Midpoint—From which there’s no going back

- Crisis—The low point, when doubt and fear are greatest

- Showdown—Where hero and villain ultimately face off

- Realization—How protagonists have changed, what they have learned

Not only that, Gurus agree that your drama should tell two stories, not one—the Action (outer) Story and the Relationship (inner) Story, each with its own set of plot points. After all, unless your hero is James Bond, he or she has feelings and foibles audience members long to identify with.

As proof that This Is the Way It Has to Be, most guru books analyze scores of well-known movie plots to point out all their Plot Points. Some even go so far as to claim that if you pop the hood of any dramatic production you will find all of the above elements in its three-act narrative engine. That’s heavy, man. Who knew? Well, it turns out that the gurus don’t credit this structure to D.W. Griffith, Eisenstein, or even Shakespeare (a five-act guy, BTW); the founder of this firm foundation turns out to be …

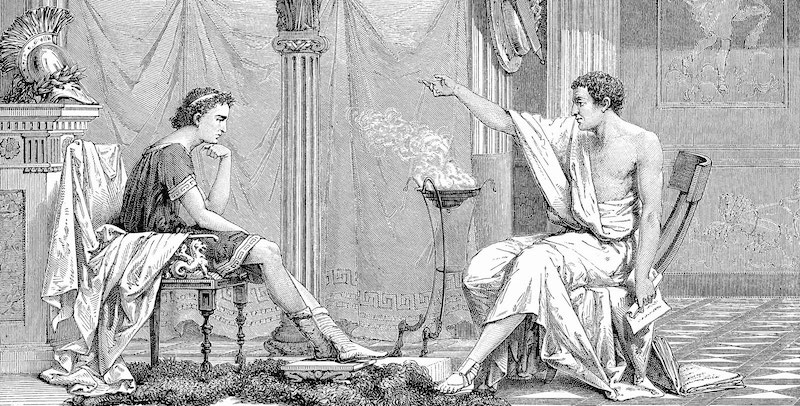

Aristotle, specifically the Aristotle of Poetics, his lectures on tragedy. Observing that all creatures are born, live a while, and then die, the Big A sagely concluded that perforce all stories involving life forms must have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Fast forward to 1979, when screenwriter Syd Field published Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting, the first widely-read how-to on the art. Field concluded from Aristotle’s rule that dramatic works should take place in three acts. As a life generally lasts longer than a birth or a death, he further opined that the second act should be the longest one. And so it came to pass that ever since Field spaketh, the Great Greek’s oversimplified dicta have been taken for gospel by most congregants of the Church of the Screenplay. (If you doubt me, you can consult this exegesis by a disciple of the field who apparently has way too much time on her hands.)

The Greek Chorus of screenwriters jangled my nerves. It peeved me that the gurus mostly tend to analyze successful Hollywood-style productions but pay little attention to films that flopped, many of which likely exhibit similar construction. Aren’t we in an endless loop inside an echo chamber? Do screenwriters cleave to the formula because studio execs say they must or because audiences demand it? If audiences demand it, perhaps it’s because that’s what all movies give them, and perhaps studios churn out hits and flops alike, thinking the standard scenario is what audiences obviously want. Notice the echo, the feedback loop, the inevitability of the sameness of it all?

Then there’s this slippery thing the industry calls “high concept.” It’s the hook, the logline, the elevator pitch that causes producers want to make and audiences flock to a film—something that differentiates it from its competition and whatever came before. (Except that high concept films apparently lend themselves well to sequels, so are the sequels just as high concept?) You can read about it in manuals and take crash courses and still not quite get it. Some gurus seem to think it boils down to a catchy title that summarizes the whole movie in one to four words, like Die Hard, Psycho, Star Wars, Finding Nemo, or (an edge case) Honey, I Shrunk the Kids. As David Trottier explains it, a high-concept concept:

- Can be easily understood by an eighth grader

- Can be encapsulated in a sentence or two

- Is provocative and big

- Bundles character plus content plus a hook

- Sounds like an “event” movie with sequel potential

- Can stand on its own without stars, but

- Will attract a big star

- Is a fresh and highly marketable idea, but

- Is unique with familiar elements

When I first heard the term, it brought to mind substantial works of art like King Lear, War and Peace, and Finnegan’s Wake that would take a fairly sophisticated eighth-grader to appreciate. It was, I naïvely presumed, the cinematic equivalent of Literary Fiction. Now that I’ve been clued in I realize that High Concept is just marquee shorthand for Potential Blockbuster that clearly begs the question of what makes a movie low-concept.

Knowing that a little bit of knowledge can be dangerous, I nevertheless decided to fashion a high-concept pitch for my novel. My logline evolved from humble origins:

Hordes of irate Zombies, sick and tired of being discriminated against, storm a phalanx of police and eat them.

Wait. That’s the wrong book. How about:

A clueless conspiracy with the courage but not the capability to take down a tyrant hatches a doable diabolical plan.

Sounds too much like comedy. Maybe I should mix that up with movie memorabilia:

The monkey-wrench gang of terrorists that couldn’t shoot straight stalks the man who would be Sultan.

Could be pithier. A nod to Pirandello, perhaps?

Six terrorists in search of an adversary

Cute, but needs a punch line, so:

Six terrorists in search of an adversary show the world that it doesn’t take much firepower to smash the state.

Or maybe pitch the narrative as one of redemption:

After conspiring with infidels to decapitate a nation, an Islamic extremist learns that articles of faith sometimes need editing.

This exercise was fun and all, but it was time to bite the bullet and whip the manuscript into shape. The best I could do was to assemble a full synopsis of the novel as I banged out its seventh revision, giving it fewer details and more pep, slimming it down by 8000 words (still too long for a feature film, so let’s hope for a miniseries). Were I to throw in an antagonist or two to spice it up, to end up with a reasonable page count some of its 150 or so scenes would have to go. It would still have way too many to pack into a movie (think 45 seconds each), but it’s so hard to decide which of my darlings to kill. And speaking of killing, I wish someone had throttled Aristotle so I wouldn’t have his botched reincarnations telling me how to thrill an audience.

Someone should pull the movies out of their faux-Aristotelian rut, and who best but a naif like me?

[…] inciting incident, protagonist versus antagonist vying for high stakes, and all that, and have said why in no uncertain terms. I look for characters whose emotions and complexities I can sink my teeth into without subjecting […]