Thanks to continuing official outrages against People Of Color piped to me by the media on almost a weekly basis, the corrosive effect of racial prejudice never strays far from my overstimulated mind. Obama’s “post-racial” presidency didn’t change hearts and minds automagically; that takes struggle, such as opposing the hundreds of GOP-filed state laws restricting voting access if not rights, which rub the salt of racism onto our civic wounds, laws that all but Republican lawmakers seem to see as targeting POC.

But racism is a slippery concept, I’ve found. And looking into the word led me to want to know more about how applying that little suffix to a noun turns a thing into a concept, if you can pin it down. Perhaps there’s a better ism to describe racial prejudice. I’ll get to that, but first, a brief tour of the wonderful, wacky world of isms.

Ism is a little noun ending that means, according to the Online Etymology Dictionary, a “distinctive doctrine, theory, or practice” at least since the 1670s, noting “the suffix -ism used as an independent word, chiefly disparagingly.” So right off the bat, to some extent, isms are objects of ridicule. Reasons for bashing isms vary, but it seems that their detractors are far more united than their proponents and their rationales for opposing a given ism are far less nuanced and coherent. Consider all the political brands those who embrace “socialism” have to choose from, while those who decry the term indiscriminately despise the lot of them.

The suffix–ism tends to occupy more neutral territory: OED (that is, the above website, not that OED) defines it as a “noun ending signifying the practice or teaching of a thing, from the stem of verbs in –izein [GR], a verb-forming element denoting the doing of the noun or adjective to which it is attached.” As I had expected, the Greeks coined it first.

You can find 322 isms listed at OED, from ableism to Zoroastrianism, many of which are breathtakingly myopic. Some of the more provincial ones include cledonism (literary), dudeism (sociological), incivism (political), melanism (medical), misoneism (cultural), naderism (eponymous), onanism (psycho-sexual), sciolism (snarky), thanatism (anti-religious), and verism (aesthetic—to which I tend to adhere, come to think of it).

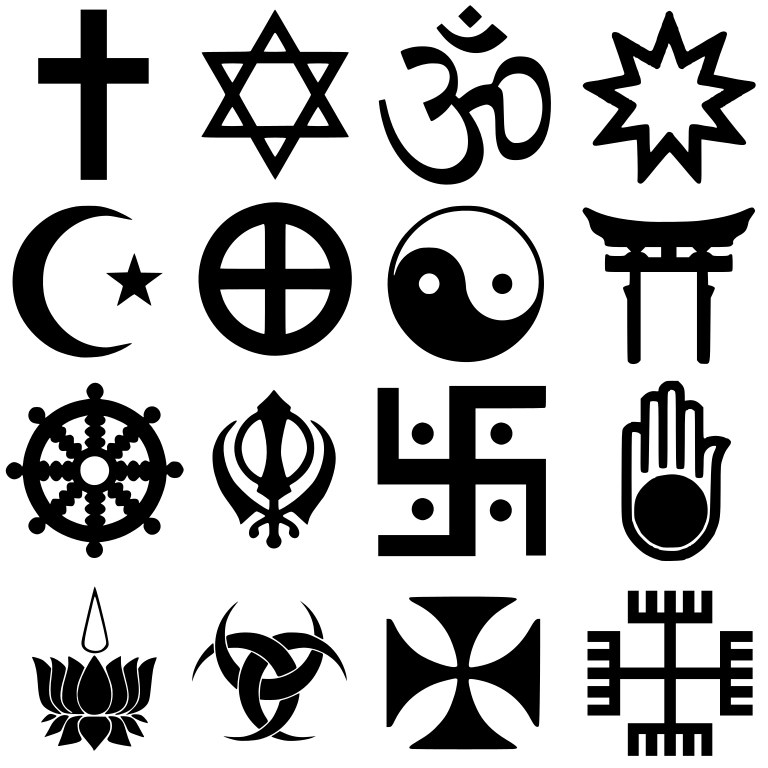

All of these are just from the English lexicon; as with idioms, other languages support many more. My off-the-cuff taxonomy above suggests that there’s little hope of constructing a searchable family tree of them. But within certain clans there are plenty of family feuds, especially those involving political, religious, and philosophical concepts.

Ontology aside, any belief or practice imaginable can be ismized, to coin a term. It can be done from within, by adherents, or from without, by skeptics and disbelievers, and the ism’s redolence will accordingly differ between the two groups.

Most any ism, old or new, can be turned on its head into something oppositional. Besides Liberalism, Unitarianism, and Alcoholism, various members of my birth family espoused anti-racism, anti-communism, plus anti-anti-Semitism. But what, pray tell, is the anti-Semitism that they opposed? Well, OED tells us that in 1848, semitic meant “characteristic attributes of Semitic languages,” and by 1851, “characteristic attributes of Semitic people,” and from 1870 “Jewish influence in a society,” Countless Christians had objections and said so, hence anti-Semitism. But there are of course non-Jewish Semites, some of whom nowadays may hate Jews even more than some Christians do. OED says that back in 1847, a Semite was a “Jew, Arab, Assyrian, or Aramaean,” or their language group. Somewhere along the line they got a divorce, which I would say was consecrated by the founding of the State of Israel.

And that goes to show how connotations can change over time and across contexts. Take what may be today’s champion ism, racism (originally racialism): A thesaurus would broadly cross-reference it to bias, bigotry, intolerance, prejudice, and xenophobia. While such habits of mind do not just pertain to racism, they are common expressions of it.

It surprised me to learn that “racism” wasn’t common parlance before Hitler rose to power to purify the “Aryan Race.” In the previous century, Americans spoke of negrophobia and Anglo-Saxonism, and abolitionists (aka emancipationists) didn’t need an ism to express the condition of black servitude they crusaded against. They focused on turning hearts and minds against the institution of slavery rather than damning the attitudes that justified it. Abolitionists themselves may have harbored such attitudes; one can condemn ownership of human beings without necessarily admitting they are equals. That is, abolitionism need not imply eqalitarianism.

When you get right down to it, while people may proudly label their own isms (think socialism, liberalism, libertarianism. conservatism), they generally rankle when someone else does it on their behalf. After all, few folks self-identify as racist or wish to be characterized as such. Were you to quiz someone who believes in the superiority of his or her own race about their underlying beliefs, you likely would be treated to religious, cultural, historical, or economic arguments about why those others just don’t properly fit into the scheme of things. Behind such rhetoric can lie an inchoate fearfulness that whatever privileges (especially if they are meager) society affords the explainer are in danger of being taken away, such that another group’s gains can only come at their own expense. This zero-sum mentality is fundamentally conservative, not that all or even most political conservatives are racist. But have not those who have perceived advantages to lose, whether money, power, or status, always tended to resist change?

Pointing to the prevalence of Korean greengrocers, Indian motel and convenience store owners, Vietnamese manicurists, and Black barbers and cosmeticians, even racists express approval of minorities “making it on their own.” If these go-getters can do it, we often hear, why can’t anyone with enough gumption and hard work flourish in the Land of Opportunity without the government favoring them over others? Aside from being psittacism (parroting ideas without reasoning) of right-wing talking points, it’s a trick question because it admits to no deliberate systemic barriers that continue to keep people “in their place,” which historically has been some kind of ghetto or job description.

As “Black Lives Matter” resounds across the nation, we hear apologists countering with the truism “All lives matter.” Those who say that likely fear cultural changes are cooking up a smaller pie for them. Best just to remind them of the even truer truism, “All lives can’t matter until Black lives matter.”

To describe this sort of negativism, need we invent a new ism? We’re looking for something that denotes “fear of racial justice.” If we broaden our sights a bit to encompass “dislike of equality,” there’s already a compound word for that: anti-egalitarianism. But a bad odor has hung over egalitarian since the excesses of the French Revolution. Perhaps we can do better.

Dig a little deeper into the American psyche and you may uncover a simmering resentment of government for proactively enforcing minority civil rights. There’s a name for that too: Dikephobia, or fear of justice (dike being the Greek root of δικαιοσύνη, “justice”), a recognized mental disorder. Replacing “phobia” with “ism” gives us dikism, signifying love of justice.

But what is justice? The word derives from the Latin iustitia “righteousness, equity,” but has accumulated contradictory interpretations. Is it “fairness,” as John Rawls put it? Is it the state’s application of “law and order,” as conservatives like to say? Founding father James Madison endorsed it without defining it (Federalist 51, 1788): “Justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society. It ever has been and ever will be pursued until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit.”

Mahatma Gandhi, founding father of modern pacifism, put it this way: “Justice that love gives is a surrender, justice that law gives is a punishment.” As must adherents of any normative ism, exponents of dikism must decide how to frame it and be prepared to live with it.

Got a pet ism, one of your own coinage, or one that you think should be a meme? Feel free to cast it into the wild in the comment section below.

Be First to Comment